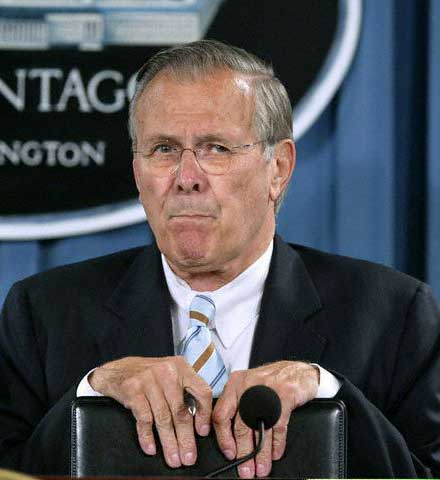

Rumsfeld, Donald

From Bwtm

- Donald Rumsfeld personally approved and directed torture.

http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction/

News

Donald Rumsfeld: Up Close and Creepy http://www.motherjones.com/mojo/2014/03/donald-rumsfeld-errol-morris-unknown-known

The Life and Times of Donald Rumsfeld

The political career of Donald Rumsfeld is vital for the understanding of what got us into the unprecedented ruin which is American foreign policy today.

"... the finest Secretary of Defense this nation has ever had." -- Vice President Dick Cheney

"The past was not predictable when it started." -- Donald Rumsfeld

On a farewell flight to Baghdad in early December 2006, the departing Secretary of Defense reminisced about his start in politics more than forty years before. Aides leaned in to listen intently, but came away with no memorable revelations. It hardly mattered. As usual with this man who dominated government as no cabinet officer before him -- including the power-ravenous Henry Kissinger he so despised and outdid in effect, if not celebrity -- authentic history and Don Rumsfeld's version of it bore little resemblance.

There was portent in those beginnings. He came out of an affluent Chicago suburb in the 1950s with brusque confidence and usable contacts at Princeton, among them Frank Carlucci, a future Defense Secretary of mediocre mind, yet the iron conceit and shrewd fealty far more effectual in government than intellect or sensibility. After college and two years as a Navy pilot, Rumsfeld did politic stints as a Capitol Hill intern and Republican campaign aide, and by twenty-nine, back in Chicago in investment banking, was running for Congress.

As with much to come, a darker thread lay beneath the surface from the start. In a Republican primary tantamount to election, he was outwardly the boyish, speak-no-evil, underfunded, underdog challenger of an old party stalwart set to inherit the open seat. In fact, he was generously financed by wealthy friends, while his operatives -- including Jeb Stuart Magruder of later Watergate infamy -- furtively harried and smeared his opponent, using tactics never traced to Rumsfeld.

He went to Washington in December 1962 a handsome, square-jawed, safe-seat tribune from the North Shore's lakeside preserves, epitomized by the leafy estates of Winnetka and high-end Evanston. The old Thirteenth District of Illinois was one of the wealthiest in the nation and had been smoothly in Republican grip for most of a century. In the House, Rumsfeld was soon seen by some as he always saw himself -- a prodigy in the dull ranks of his Party.

Then, as afterward, he had no authentic qualifications or independent achievements. But that was always masked by the same muscular, aggressive style he took onto the mat as an Ivy League wrestler -- "sharp elbows," a meeker, envious colleague called it -- as well as by the flaccid banality of most of the GOP in the 1960s. The Republican Party Rumsfeld strode into was already caught between the wasting death of Eisenhower worldliness and moderation (with Richard Nixon's haunted succession in the wings) and a fitful right-wing urge to seize control that, in little more than a decade, would deliver the Reagan Reaction.

Rumsfeld's own rightist mentality, his New Deal-phobic corporatist cant and Cold War chauvinism, came dressed more in modish vigor than telltale substance -- and he was already attracted by a tough-minded layman's zeal for the era's pre-micro-processing but grandly prospering military technology. Like most of his generation born in the early 1930s, the scrap-drive, victory-bond children of World War II who came to govern the postwar world and would be the decisive elders of the post-9/11 era, he had no doubt about the natural nobility of America's sway or the invincibility of its arms; all this made ever sleeker, ever more irresistible by the demonstrable twin deities of American capitalism -- technology and "modern" management.

That, after all, was the unquestioned, unquestioning faith of North Shore fathers and other successes like them across the nation. That was the world, according to postwar Princeton, as well as Harvard Business School. That was the supposed genius of future Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara's duly quantified Ford Motor Company as well as his Vietnam-era "systems analysis" Pentagon, and so much more.

In the early 1960s, that received world ended just beyond the suites and suburbs. Given America's moral and material omnipotence, its exemplary excellence (so evident on the North Shore), the remainder of the planet required no particular exploration, knowledge, or historical-political understanding, nor did such men need to have the slightest recognition of America's own non-mythologized past. Alert decision-makers, busy with the numbered bottom-line results, had no time for such "academic" ephemera.

When money or force needed to be applied to Asians, Arabs, Latins, or Africans, a crisp briefing by some underling who had read the necessary memos would always do. Caught up as we all have been in Rumsfeld's kinetic, churlish descent into the bloody chaos of his Iraq, it has been easy to neglect how richly cultural it all was from the beginning -- America's haunted half-century of vast might and presumption set beside our still vaster ignorance and irresponsibility. It was in 1963, during Don Rumsfeld's first months in Congress, that the Iraqi Ba'ath Party -- since 1959 recruited, funded, marshaled and directed by the CIA, and trailing a twenty-six-year-old Tikriti street thug named Saddam Hussein (himself a CIA-paid assassin) along with lists of hundreds of left-leaning Iraqi political figures and professionals to be murdered after the coup -- seized power in Baghdad.

On Capitol Hill, the spirited young Republican legislator was then absorbed in exhilarating new appropriations in aeronautics and weaponry. His trademark clipped fervor and biting sarcasm in questions and speeches already held a hint of the Pentagon E-Ring canon four decades later: the superpower military as classic wrestler -- lithe, superbly equipped, swift to pin a dazed foe, dominant beyond doubt, and with garlands all around. It was only a matter -- he began to learn early from helpful briefings and testimony by military-industrial executives -- of making the commanders (the branch managers, after all) change their sluggish old ways. The by-word would be: Procure to prevail. So superior was new technology and the management that went with it that it scarcely mattered who the competitor might be. In those long-gone days, in obscure Washington hearings unheard, in colloquies before empty chambers, there were the first faint drums of distant disaster in the Hindu Kush, Mesopotamia, and beyond.

Of course, in the 1960s, Rumsfeld's ardor for a high-tech military was only stirring, a minor dalliance compared to his preoccupation with advancement. While few seemed to notice, the brash freshman made an extraordinary rush at the lumbering House. In 1964, before the end of his first term, he captained a revolt against GOP Leader Charles Halleck, a Dwight D. Eisenhower loyalist prone to bipartisanship and skepticism of both Pentagon budgets and foreign intervention. By only six votes in the Republican Caucus, Rumsfeld managed to replace the folksy Indianan with Michigan's Gerald Ford.

In the inner politics of the House, the likeable, agreeable, unoriginal Ford was always more right-wing than his benign post-Nixon, and now posthumous, presidential image would have it. Richard Nixon called Ford "a wink and a nod guy," whose artlessness and integrity left him no real match for the steelier, more cunning figures around him. To push Ford was one of those darting Capitol Hill insider moves that seemed, at the time, to win Rumsfeld only limited, parochial prizes -- choice committee seats, a rung on the leadership ladder, useful allies.

Taken with Rumsfeld's burly style that year was Kansas Congressman Robert Ellsworth, a wheat-field small-town lawyer of decidedly modest gifts but outsized ambitions and close connections to Nixon. "Just another Young Turk thing," one of their House cohorts casually called the toppling of Halleck.

It seems hard now to exaggerate the endless sequels to this small but decisive act. The lifting of the honest but mediocre Ford higher into line for appointment as vice president amid the ruin of President Richard Nixon and his Vice President, Spiro Agnew; Ford's lackluster, if relatively harmless, interval in the Oval Office and later as Party leader with the abject passing of the GOP to Ronald Reagan in 1980; Ellsworth's boosting of Rumsfeld into prominent but scandal-immune posts under Nixon; and then, during Ford's presidency, Rumsfeld's reward, his elevation to White House Chief of Staff, and with him the rise of one of his aides from the Nixon era, a previously unnoticed young Wyoming reactionary named Dick Cheney; next, in 1975-1976, the first Rumsfeld tenure at a Vietnam-disgraced but impenitent Pentagon that would shape his fateful second term after 2001; and eventually, of course, the Rumsfeld-Cheney monopoly of power in a George W. Bush White House followed by their catastrophic policies after 9/11 -- all derived from making decent, diffident Gerry Ford Minority Leader that forgotten winter of 1964.

Burial party

They were Nixon men. Rumsfeld and Cheney rose via the half-shunned political paternity of a cynical president who abided and used some he distrusted, even came to deplore. Brought into Nixon's 1968 presidential campaign through Ellsworth's influence, Rumsfeld fell into an opportune role -- spying on the Democratic Convention in Chicago, which exploded in the infamous "police riot" against antiwar demonstrators that tore apart the Democrats and lent the spy's reports unexpected gravity. (Among faces in the crowd watching the mayhem was another onlooker out of a comfortable Republican suburb, a twenty-one-year-old Wellesley student from Park Ridge named Hillary Rodham.) Though he gained attention in the Democrats' disaster, Rumsfeld ran up against Nixon's equally barbed campaign manager, Bob Haldeman and, despite their election victory, returned to Congress in 1969 without reward.

Bipartisan collusion rescued him. By 1968, President Lyndon Johnson's four year-old Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), the heralded antipoverty program with its grassroots "Community Action" and its Legal Services for the poor, had become a potential success story -- and thus anathema for powerful Democrats as well as Republicans. Denied a 1964 cigarette tax (that would have funded it securely) by the tobacco lobby, then starved by the sinking of resources into the maw of the Vietnam War, OEO was ultimately doomed when the nascent political, economic, and legal assertiveness it nurtured among the thirty to fifty million dispossessed threatened the hold of vested-interest donors and the mingled power bases of governors and mayors, congressmen and legislators of both parties. As early as 1966 they began trooping in numbers through the Old Executive Office Building -- liberal and conservative but uniformly self-preserving, the single party of incumbent power -- to lobby Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who planned to cut the program when he himself became president.

With Nixon's victory over Humphrey, OEO's death became a certainty, though a tough infighter was needed as director to take out the agency's life support systems. Nixon first ignored the appointment; then, later in 1969, at the urging of ranking Senate and House Democrats as well as Ford and Ellsworth, named Rumsfeld to the post. He, in turn, chose as his deputy Princeton pal Frank Carlucci, already off to a buccaneering start in the Foreign Service amid early 1960s CIA coups and assassinations in the Congo. The writ was plain. On Capitol Hill, they called Rumsfeld "the undertaker."

So it was that a slight, already balding 28 year-old Republican Congressional intern, Richard Bruce Cheney, soon steered to the new OEO Director a 12-page memo setting out how to run the agency in a way that would kill what they all deplored. Cheney had failed at Yale. Returning to his native Casper to work as a telephone lineman, he eventually went to college in Wyoming and, avoiding the Vietnam draft like the plague, on to graduate school and a DC internship meant to satisfy his ambitious fiancée Lynn and to retrieve a white-collar career. Like so many in the neo-conservative swarm he came to head after 2001, Cheney brought to public life no intellectual distinction or curiosity, and certainly no knowledge of the wider nation and world. Washington in 1968 marked the first time he had lived in a town of more than 200,000.

Over his glacial insularity, though, lay a reassuringly phlegmatic manner. In Washington, he found he had an instinct for the quiet, diligent subordinate's exploitation of institutional indolence, and he brought with him a clenched-teeth, right-wing animus that more visible Republicans judged impolitic to express but impressive in a backroom staff man.

"Dick said what they all thought but didn't say aloud," a Hill aide (and later Congressman) recalled of often raw conversations about money, race, partisanship, and particularly Cheney's angry, acid scorn for college antiwar protests that gave reassuring voice to the publicly muted abhorrence of Republican politicians. Having earlier rejected him as a House intern, Rumsfeld now made the young right-winger his key personal assistant at OEO, where he proved devotedly efficient. The hiring brought three future Secretaries of Defense -- Rumsfeld, Carlucci, and Cheney -- into the same office, toiling to abort the unwanted embryonic empowerment of the poor.

When they became celebrities, there would be much written about how the styles of Rumsfeld and Cheney meshed - Rummy's sheer brio, his relishing combat and the limelight, his free-wheeling way of sparking ideas and decisions helter-skelter (his famous routine of dropping to the floor for one-arm push-ups, a tic that a bureaucrat-benumbed Washington media always found fetching); and steady, backroom Dick, the methodical organizer, the modest detail man seeing to practical execution.

Close up, the bond was even deeper. Across an age gap of almost a decade, despite the distance between charged and calm, North Shore and Casper, Princeton and Wyoming, country club Congressman and lumpen-proletarian repairman, they shared something rarely then so openly admitted on the right: an abhorrence of the liberations sweeping the 1960s, not just the right's pet scourges of bureaucracy, crime, drugs, social fragmentation, and (however suitably coded) racial integration, but the unsettling ferment of newfound freedoms and honesty, the defiance of cultural and institutional oppressions -- especially by minorities and women. They detested Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, the way it seemed to advance beyond the New Deal and Progressivism at the expense of settled money and power.

Altogether it was a moment of hurtling change that many saw as ominous weakness and laxity, of new public programs for the long-excluded, which the world of Rumsfeld and Cheney imagined as "socialism." For them, the balancing regulation of long-dominant business power was nothing short of "tyranny"; the new arrangements of race and class, the myriad threats of sheer liberty in a more equitable society and economy, were menacing.

Whatever their other ties, Rumsfeld and Cheney were two of the era's visceral reactionaries in the classic sense of the term. Musing with younger aides on one of his last days in the White House, Johnson came up with a telling term for their ilk. "The haters," he called them. "They hate what they can't run any more" was the way he put it. The calamity Rumsfeld and Cheney later wrought in American foreign policy traced not only to profound ignorance and immense, careless pretense about the world at large, but in some part to a four-decade-old kindred fear and loathing at home.

OEO began the Rumsfeld myths. "He saved it," Carlucci would blithely tell oblivious post-9/11 reporters hardly apt to check the actual fate of the agency. Carlucci would spin an image of an ever-energetic Rumsfeld taking up the cause of the needy, streamlining and fortifying the laggard agency despite the funeral that had been ordered. It was a blasé postmortem lie. Community Action, Head Start, VISTA, Job Corps, and most decisively Legal Services (whose leadership Rumsfeld and Cheney together decapitated in 1970) -- one by one, each of these beleaguered efforts was stifled or sloughed off to political sterility. This mission, at least, was accomplished. By the time the burial was complete -- with the agency's quiet extinction in 1973, unmourned by the powers of either party -- the undertaker had moved on to higher office.

In 1971, Nixon had been stymied in his plan to use Rumsfeld in a cabinet shakeup and so took him into the White House as a domestic affairs "counselor." The Rumsfeld White House interval over the next two years is captured on Nixon's infamous secret tapes. With his ever-aggressive, if not megalomaniacal, 40 year-old aide, the 60 year-old president adopts an avuncular tone, while Rumsfeld angles brazenly to supplant Henry Kissinger as a special envoy on Vietnam or even to replace Vice President Spiro Agnew on the 1972 ticket. Patiently, yet with audible derision and occasional incredulity, Nixon suggests seasoning in more modest positions. Thus, after the president's 1972 reelection triumph, an eager Rummy would be made ambassador to NATO, spoils previously in the hands of their mutual friend Ellsworth, who urged Rumsfeld for the job.

It all yielded more myths, more confected history by a submissive, uninformed media profiling post-9/11 power. There would be the image of Rumsfeld as White House "dove" on Vietnam, when his bent was exactly the opposite; or that Nixon, it would be claimed, saw him as uniquely in touch with the diversity of the country, especially the young -- when the reality was that Rumsfeld, having served an impatient three terms from his lavishly unrepresentative rotten borough of Winnetka wealth, with his generic contempt for the 1960s and his part at OEO suppressing the emergence of millions of the young poor, was anything but.

At the time, privately at least, his grasping shallowness led to withering -- now long-forgotten -- verdicts from knowing witnesses. Even a jaded Nixon would eventually deplore him as "a man without idealism." His extensive experience with despots giving the judgment added weight, Henry Kissinger came to think Rumsfeld the "most ruthless" official he had ever known.

In a Washington that routinely hides its ugly inner truths of character and incompetence, none of it mattered. Away at NATO in Brussels, frustrated by multinational diplomacy but expanding his own sense of political-military mastery, Rumsfeld managed to escape the Watergate incriminations of 1973-74. Instead, he seemed like a fresh face when Gerald Ford succeeded the disgraced Nixon in August 1974. Anxious to be rid of Nixon co-conspirators like then-White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, but facing a period of rule with inadequate crony aides, the earnest new president called back clean, hard-charging Don to be his chief of staff. Rumsfeld promptly brought in Cheney, just on the verge of vanishing mercifully into private business -- and the rest is history.

Massacres

Barely a year after moving next to the Oval Office (and contrary to Ford's innocent, prideful recollection decades later that it was his own idea), Don and Dick characteristically engineered their "Halloween Massacre." Subtly exploiting Ford's unease (and Kissinger's jealous rivalry) with cerebral, acerbic Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, they managed to pass the Pentagon baton to Rumsfeld at only 43, and slot Cheney, suddenly a wunderkind at 34, in as presidential Chief of Staff.

In the process, they even maneuvered Ford into humbling Kissinger by stripping him of his long-held dual role as National Security Advisor as well as Secretary of State, giving a diffident Brent Scowcroft the National Security Council job and further enhancing both Cheney's inherited power at the White House and Rumsfeld's as Kissinger's chief cabinet rival. A master schemer himself, Super K, as an adoring media called him, would be so stunned by the Rumsfeld-Cheney coup that he would call an after-hours séance of cronies at a safe house in Chevy Chase to plot a petulant resignation as Secretary of State, only to relent, overcome as usual by the majesty of his own gifts.

With such past trophies on their shelves, it would never be a contest for Rumsfeld and Cheney after 2001. That fall of 1975, 29 year-old George W. Bush, the lineage's least fortunate son, was in Midland, Texas, partying heartily and scrounging for some role on the rusty fringes of the panhandle oil business.

By December 1975 having pushed aside Watergate-appointed Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, the longtime abomination of the Republican right, Rumsfeld was already positioning himself to be Ford's 1976 running mate -- and eventual successor. But that spring Ronald Reagan came so close to wresting the nomination from Ford, with primary victories in North Carolina and Texas, that the President's other advisors, many of whom detested Rumsfeld anyway, sprang to appease the Reagan camp by persuading the President to put choleric right-wing Kansas Senator Bob Dole on the ticket instead.

Among those advisors was George H.W. Bush, then-CIA Director. (He had gotten the job thanks to a cynical recommendation from Rumsfeld, calculating that to put Bush at the scandal-ridden agency would eliminate him as a potential rival). Another was Bush's onetime Texas campaign aide, a moneyed corporate lawyer and would-be power-broker from Houston, and now an obscure Commerce Department official who became Ford's 1976 campaign manager, James Baker III. It was an adroit back-corridor move, the sort Rumsfeld himself had been practicing so adeptly, and it embittered him for years toward his old patron Ford as well as Bush, Baker, and others -- one more wisp of a seamy, unseen history, of customary Republican cannibalism that wafted ironically over the last days of 2006 with Baker's Iraq Study Group and the Ford funeral.

Designs on the Oval Office thwarted but by no means given up, Rumsfeld spent scarcely fifteen months at the Pentagon in 1975-1976, but they were quietly, ominously historic. It was an interval, however brief, that proved far more significant and premonitory than commonly portrayed. In many ways, it both foreshadowed 9/11 and prepared the way for the fateful sequel to it.

At every turn, the new SecDef pulled policy to the right -- aligning Washington even more egregiously than usual with reactionary regimes in Asia and Latin America, smothering the nation's only serious attempt at intelligence reform, beginning the demolition of détente with Russia that would climax in its extinction under Jimmy Carter. At home and abroad, Rumsfeld seeded the Middle East for future crises and, even more insidiously, joined the military leadership in cravenly abandoning the post-Vietnam battlefield of historical understanding and institutional change.

In his first days in office, he quickly allied himself with the longtime (but until then vain) efforts of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to stall the pending Strategic Arms Control Agreement with Moscow. He also pushed Kissinger and Ford into one of the more disgraceful acts of that presidency (discreetly ignored in the recent Ford retrospectives) -- the assuring of the Indonesian military junta that U.S. support and arms would continue to flow, despite the brutal suppression about to be unleashed on East Timor.

It was only a taste of the Rumsfeld preference for uniformed right-wing tyrants, indulged over the next year in an ever closer Defense Department liaison with military dictatorships in Latin America, most notably through Operation Condor, joint covert actions involving several regimes, among them Gen. Augusto Pinochet's Chile and the Argentine military dictatorship, with Pentagon attaches and intelligence advisors looking on approvingly. The result was a plague of kidnappings, disappearances, and assassinations throughout the Hemisphere, including, in 1976, the brazen car bomb murder of former Chilean Foreign Minister Orlando Letelier and an American colleague on Massachusetts Avenue in downtown Washington. Unfailingly backed and expanded by Rumsfeld, the collusion with Indonesian and Latin American despots underwrote more than a decade of some of the most savage repressions of the second half of the twentieth century.

The customary Pentagon-State Department bureaucratic war Rumsfeld waged against Kissinger (with a vengeance fired by the Defense Secretary's presidential ambitions) involved a furtive alliance with Capitol Hill's ubër-hard-line Democrat, Armed Services Committee Chairman (and Kissinger nemesis) Henry "Scoop" Jackson. A Washington State backwoods, shoreline-county prosecutor, he had become the "Senator from Boeing." Jackson's Russophobia, demagoguery on arms control, and zealous backing of Israel (especially on the then-charged issue of Jewish emigration from the USSR) would land Rumsfeld in the milieu of the Israeli lobby, already formidable if only a kernel of the special interest colossus it would later become.

Jackson's Cold War mania was fattening military budgets along with the requisite Puget Sound contracts, not to speak of the senator's own war chest for a 1976 presidential run, and all this was being fomented by a bustling, pretentious, pear-shaped young Jackson aide named Richard Perle. Perle's somber, if oily, manner hid his own considerable lack of intellect or knowledge about either Russia or the Middle East, but his hard-line anti-Soviet and Zionist zeal gave him, as Jackson's policy broker in the politics of the moment, a cachet and following far beyond his meager substance. Rumsfeld's collusion with Jackson would thus introduce him to some of the still marginal publicists, ideologues, and Washington hangers-on who would take the term neoconservative as the label for their career-plumping chauvinism and, less audibly, their tragically intermingled allegiances to right-wings in both the U.S. and Israel.

In Rumsfeld's early tie to this wanna-be-establishment claque were omens of the history they would make together after 2001. It was his "sharp elbows" that were thrown to create the notorious "Team B," a collection of incipient neocons and Russophobes in and out of government, including Paul Wolfowitz. They were summoned to offer a fearsome analysis of Soviet capabilities and intentions that would be an alternative to comparatively unfrightening (and accurate) CIA assessments being attacked by Ronald Reagan and his right-wing minions in the 1976 campaign. In this surrender to election-year demagoguery could be found the hands of the White House and the elder Bush at the CIA (more Ford regime shame politely forgotten in the mournful, anxiety ridden, anyone-compared-to-George-W. fin de 2006 moment), but Rumsfeld's role was crucial -- and the consequences historic.

The absurdity and ideological corruption of Team B's "analysis" of the Soviet bogeyman (along with a desired future confrontation with China, a nakedly racist, essentially right-wing Israeli view of the Arab world, and a refusal to face the Vietnam defeat) would be plain even then; though decades later, the post-Soviet archives would definitively reveal it for the fraud it was. As it was meant to, it fed the massive arms buildup of the Reagan 80s, and with it the engorging of the military-industrial colossus that, in turn, filled Republican campaign coffers. And all of this, of course, including the ensuing distortions in domestic priorities, would pave the way for Rumsfeld's eventual return to power.

The "Team B" scandal also foreshadowed an insidious post-9/11 plague, the right-wing assault on relatively non-ideological national intelligence that was to lead to the blatant substitution of alternative "intelligence" operations in Rumsfeld's Pentagon and Cheney's vice-presidential office (full-time versions of "Team B," as it were), as well as the coercion and corruption of conventional CIA channels.

In 1976, Rumsfeld worked assiduously to undercut any intelligence that challenged his right-wing bias and, with Cheney helpfully in the background at the White House, fought hard to drown any meaningful intelligence reforms after mid-1970s hearings chaired by Senator Frank Church and Congressman Otis Pike offered shocking revelations of CIA covert-operations abuses. The resulting half-measures and truncated accountability sent unmistakable signals through Washington, setting the stage for various CIA rampages of the 1980s under Reagan campaign manager William Casey (and one of Casey's ambitious, agreeable aides named Robert Gates). The direct consequences in blowback and loss of professional integrity would be felt for decades to come.

Then, there was the Middle East. In mid-1976, exiled Palestinians allied with a Lebanese nationalist coalition to politically and economically challenge the traditional privileged rule of the West's Christian-dominated client regime in Beirut. Faced with this, the Secretary of Defense was decisive in the secret US-Israeli instigation of a Syrian military intervention meant to thwart both the Palestinians and the Lebanese rebels. Rumsfeld muscled the covert action through, despite Kissinger's initial hesitation. It ushered in a three-decade-long Syrian occupation of Lebanon, with relentless machinations in the Levant involving the Israeli intelligence service, the Mossad, the CIA and, beginning under Rumsfeld as never before, the Pentagon's Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA).

Already significant in the 1950s, the CIA-Mossad collaboration in Lebanon and elsewhere certainly pre-dated Rumsfeld, and crucial decisions in the deepening collusion would come after him. But the 1976 intervention, which he backed so strongly, would take the complicity to a new level, with a twisting sequel of tumult and intrigue that directly paved the way for the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and thus for the eventual rise of Hizbullah.

At the same time, Rumsfeld avidly stepped up ongoing U.S. arms shipments to the Shah of Iran's corrupt, U.S.-installed oligarchic tyranny -- its torture-ready SAVAK secret police intimately allied with the Mossad, the CIA and the DIA. In 1976, Rumsfeld also pressed the sale to the waning Shah of up to eight nuclear reactors with fuel and lasers capable of enriching uranium to weapons grade levels. Ford was prudently uneasy at first, but relented under unanimous pressure from his men. Cheney backed Rumsfeld from the start in urging an Iranian nuclear capability; and, in this at least, they were joined by their arch-rival Kissinger, ever solicitous of his admirer the Shah, ever oblivious to internal Islamic politics - he himself primed by an obscure but vocal thirty-three-year-old State Department aide named Paul Wolfowitz.

At its Rumsfeldian peak in 1976, U.S. weapons and intelligence trafficking with the rotting Iranian imperial regime took up the time of some eight hundred Pentagon officers. Barely two years later, the Shah's regime would fall to the Ayatollah Khomeini's Islamic Revolution, in part under the sheer weight and waste of the Pentagon's patronage. Like CIA-DIA connivance with SAVAK -- which included coordinated assassinations of Iranian opposition political figures or clerics and, in 1977, even Khomeini's son -- Pentagon complicity with the hated old order made all but inevitable the widespread anti-American sentiment in Iran that would in the future be so effectively exploited by the Islamic regime's propaganda. Detonating in the 1979 seizure of U.S. embassy hostages in Tehran, popular Iranian hostility would burn out of a history of intervention and intrigue few Americans ever knew the slightest thing about.

In this way, Rumsfeld and others, including Gates and his slightly mad patron Casey at the CIA, would all, in some degree, become policy godfathers of the mullahs' regime in Tehran as well as of Hizbullah.

"The Dark Ages"

Even more costly would be the toll the Rumsfeld interregnum would exact deep inside the American military. However brief, Rumsfeld's mid-1970s rule over the Defense Department proved, in certain respects, the most crucial moment at the Pentagon since World War II. In seven tumultuous years from Johnson's fall to Nixon's, spanned by defeat and de facto mutiny in Vietnam, four secretaries would troop through Defense, each consumed by war or politics, none engaging the institution's historic plight.

Taking office six months after the fall of Saigon, Rumsfeld would inherit the first truly post-Vietnam military. Fittingly, the institutional crisis he faced had come into being over the full two decades of his adult life since the 1950s. By the time he settled in at the Pentagon, that crisis had already been extensively studied and well documented. Conclusions were available for the asking -- or hearing or reading -- in any Pentagon ring, at any military post at home or abroad as well as in Congress, the White House, and the press, not to speak of the American public. It was unmistakable in the searing experiences of a war whose dark-soil graves at nearby Arlington were still fresh.

By any measure, Rumsfeld arrived at a rare, and exceedingly fleeting moment when the enormous U.S. war machine might have come to terms with its past, and so the future. The failure to do so -- hardly Rumsfeld's alone, but his role was decisive -- would haunt America and the world into the twenty-first century.

Vietnam had laid bare the malignant decaying of America's armed forces that began in the wake of their first unwon war in Korea. There was "no substitute for victory," General Douglas MacArthur had written a Congressman in the letter that finally prodded President Harry Truman to fire him as commander of U.S.-U.N. forces in Korea in 1951. The services nonetheless promptly found a perfectly reasonable substitute -- for a while -- in the warm bath of a careerist managerial ethic.

Ruled in World War II by an ever-growing bureaucracy, ever more inhospitable to the officer as individual, America's superpower military was, as the Korean War began in 1950, already a sclerotic giant. "A glandular thing" was how Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett would describe it a decade later to John Kennedy. The brutal Korean stalemate, following on the early rout of a billet-flabby, semi-demobilized occupation army from Japan, and later the frozen, bloody retreat from a heedless, MacArthur-led advance to conquer North Korea right up to the Chinese border, added to the curse.

Faced with the demanding, unnerving politics of a nuclear-armed peace, a supposedly matchless force met its match in Korea not just on the battlefield, but in the murky realms of political sophistication. In response, grappling to redefine its place (and reassure itself at the same time), the military in the 1950s came to produce a preponderance of what one critic called the "formlessly ambitious" officer; one who saw climbing the military ladder like ascent in any other corporate culture. To a blight that Charles de Gaulle once deplored in his French Army as "solely careerism," the post-Korea U.S. military added the fetish and pseudoscience of "management" -- warriors astride desks, commanding paper flow and brandishing the numerology of budgets with ever-more expensive weapons systems.

Procurement plunder and corruption, the venal revolving door between senior officers and corporate contractors, the inveterate lack of authentic accounting and accountability at almost every level -- all the old Pentagon scourges now ran rampant. The good staff life rather than active command, "ticket punching," the right job at the right time -- all of this fostered an officer corps overwhelmingly pursuing rank as an end itself, at pains to do no more than what one embittered combat colonel recalled as "a necessary but minimal amount of field duty."

As credentials merely accumulated, as efficiency reports inflated and grew meaningless, there was the inevitable atrophy of ethics and the military art. Oddly enough, management itself, the faith and practice of the new creed, was the first casualty of institutional shallowness and self-protection. Winners emerged compromised and cynical; losers, alienated and contemptuous of superiors. General morale, credible command authority, and old-fashioned élan as well as esprit de corps were decimated in the process. Graduates and non-graduates alike trained their disillusion on institutions like West Point, which, by the early 1960s, many privately mocked as the South Hudson Institute of Technology -- SHIT. The Academy's sacred "duty, honor, country" now seemed eclipsed in practice by any mammoth organization's immutable rule of survival: Cover your ass.

Despite the need to understand the history and politics of vast new arenas of American policy -- regions of potential military embroilment such as Asia or the Middle East -- once-elite service graduate schools like the War Colleges became what one study termed "usually superficial and vapid." There would be no twentieth-century American Clausewitz, wrote Ward Just, the best of the era's military-affairs journalists, surveying the wreckage of a defense establishment driven by corporate inanity, "because the writing of Von Krieg (On War) took time and serious thought."

Much of this bureaucratic decadence overtook other arms of government in the 1950s, not least the State Department. As Vietnam soon would prove, however, a craven ethos and command mediocrity in a military -- whose business, as Korea savagely reminded everyone, is sometimes to fight wars -- would be catastrophic.

Within the system, there were predictable if vain attempts to hide the approaching disgrace. When, in 1970, a war-college study of "professionalism" in Vietnam was done with implications (as a pair of reviewing experts described it) "devastating to the officer corps," the Joint Chiefs of Staff quickly classified and suppressed the findings. Yet none of the inner withering was a secret, or even arcane knowledge, in government. Before, during, and after Rumsfeld's first regime at the Pentagon, Congressional hearings, journalism and memoirs exposed the reality for what it was; while nationally noted, amply documented books, often written by veteran officers or based on their testimony, appeared under titles that spoke eloquently of the disaster still to come: Crisis in Command: Mismanagement in the Army, Defeated: Inside America's Military Machine, Self-Destruction: The Disintegration and Decay of the United States Military, The Death of the Army.

Vietnam nearly made the figurative death literal. Ironically, there had been a portent of the debacle ahead in Southeast Asia (and of Iraq and Afghanistan 30 years later, for that matter) in a book discussed in Washington to the point of fad just as Rumsfeld began his political career in the early 1960s.

General Maxwell Taylor was a handsome, much-decorated World War II airborne hero, a Missouri country boy who became a reputed military intellectual, albeit given to the pandemic provincialism yet gall typical of postwar American officialdom, whose nation's new world power so outstripped its knowledge of the planet. The general could thus unabashedly extol the Shah's repressive Iranian troops as among the "armies of freedom," and instruct a West Point class on the eve of Vietnam that they were entering a world in which "the ascendancy of American arms and American military concepts is accepted as [a] matter of course."

More grandly, Taylor proposed to correct the errors of the key strategic doctrine of the Eisenhower presidency, the policy of "massive retaliation" in which America's overwhelming nuclear superiority -- its bombers ringing the USSR and China, some within minutes of their targets -- was to deter any move by Soviet or Chinese forces across the Cold War's post-Korea established boundaries. That strategy might keep the Red Armies in their kennels, Taylor argued, but it was hardly a response to campaigns waged by proxy communists on the periphery in the Third World.

To meet that threat -- and, not incidentally, to rescue his beloved Army from the mission and budget predations of the nuclear-armed Air Force throughout the 1950s -- Taylor proposed a new orthodoxy of "limited wars," adding to nuclear deterrence a "strategy of flexible response." He defined his breakthrough in a celebrated book, Uncertain Trumpet, as "the need for a capability to react across the entire spectrum of possible challenge for coping with anything from general atomic war to infiltration and aggressions..."

On whether the United States could practically, or should politically, as a matter of national interest cope "with anything," the confident paratrooper Taylor wisely did not elaborate. His point, after all, was at heart a bigger, better army with bigger better budgets. Properly selected "limited wars," with newly created forces chafing to be used, would presumably take care of themselves. But Taylor at least did warn that it would be necessary "to deter or win quickly," dictating an overwhelming application of men and weaponry and a victory so swift and decisive that everyone, including the defeated enemy, would accept it. "Otherwise," he noted ominously in a passage the general as well as his admirers later tended to overlook, "the limited war which we cannot win quickly may result in our piecemeal attrition."

Minus this gloomy caveat, Taylor's theme enjoyed swift vogue in the early 1960s -- with both Republicans and Democrats eager to engage what were seen as ubiquitous Russians and native communists scavenging post-colonial turmoil in the Third World. Among them were right-wingers like Rumsfeld, impatient with the aged caution of the Eisenhowers and Hallecks in their own Party, and among the Democrats, President John F. Kennedy himself. He promptly made Taylor a ranking advisor on Southeast Asia and other matters. Crippled by careerism, the military thus readied itself to fight in reassuring theory what in Vietnamese reality would be Maxwell Taylor's oxymoronic nightmare -- a limited war of attrition.

That war, of course, had its men of courage and integrity. More than ever, though, they were the exceptions to the prevailing system, and few of them made it as intact survivors to highest rank in the twenty-first century. The machinery that in peacetime routinely ground out rhapsodic officer efficiency reports instantly applied the same practiced reflexes to the surreal paper work of Saigon and its offshore carrier groups, fattening Vietcong body counts, bombing damage assessments, and accounts of South Vietnamese client efficacy that seemed to prove victory ever on the way. When intelligence reports discovered awkward enemy strength and resilience or detected unwanted signs of another losing war, they were simply falsified, destroyed, or buried.

The massively beribboned chests of commanders in Iraq and Afghanistan three decades later, many of whom had been junior officers in Southeast Asia, would be unintended reminders of how much the Vietnam fraud fed on even the old honor of citations. Like a debased currency, ribbons for courage or exceptional service lost value as they accumulated, with awards snidely known as "gongs" and oak leaf clusters as "rat turds." Once-respected air medals (800,000 of them) were handed out for almost any non-combat flight in that helicopter-swarming war, or even for hauling holiday frozen turkeys snugly behind the lines.

Decorations were heaped so bountifully on generals along with lesser staff officers that valor in such numbers, wrote one combat veteran, was "incomprehensible." To Vietnam's "grunts," as they related again and again, the war was too often fought with their officers 2,000 feet up in the comparative safety of "eye in the sky" command helicopters rather than with their "ass in the grass" with their troops.

Casualty figures were telling. In over a decade of fighting, with over 58,000 American dead, only four generals and eight colonels fell in combat. Commissioned rank was a guarantee of survival as for no other modern military at war (save perhaps in Iraq and Afghanistan in figures yet to come, but where we know high ranking officers were seldom at the front). "The officer corps simply did not die in sufficient numbers or in the presence of their men often enough," concluded two postwar analysts of the army's resulting "crisis."

With the corruption of standards came an inevitable loss of morale. To soldiers of honor at every level the ignorance, self-protection, and widespread opportunism of so many superiors made Vietnam what one colonel called "the dark ages in the army's history." Through the ranks, unprecedented, ran the unchecked contagion of disintegration -- refusal of orders amounting to mutiny; desertions in the tens of thousands; a drug epidemic and race riots; uncounted, unaccountable atrocities; and not least the assassination of officers and noncoms by their own men.

The American military's internecine murder acquired its own ugly Vietnam name, "fragging." Among the officer corps, according to a war-college appraisal, there had been "a clear loss of military ethic," not to be explained simply by a largely citizen-soldier, draft-dependent army. Altogether, another study concluded still more clinically and bluntly, the Armed Forces in Vietnam bordered on "an undisciplined, ineffective, almost anomic mass," its commanders high and low manifesting "severe pathologies."

Added to the war's vast profiteering and waste, all this spurred an exodus of disillusioned military professionals (unprecedented and unmatched until the Iraq War), depriving the services of most of their most promising young leaders. It also produced by 1975-1976 an unparalleled outpouring of public and internal criticism with often shocking revelations by officers, enlisted men, and other knowledgeable observers in and out of government.

The great evasion

Yet atop the Pentagon at the immediate postwar height of the now furious, anguished outcry -- what an admiral witnessing it called a "real rebellion of the heart" -- Rumsfeld took no meaningful part in the airing or soul-searching; nor did he take control of, or cleanse, the pestilent contract and accounting scandals. What he did was effectively ignore, dismiss, or on occasion repress and even punish critics and whistle-blowers.

Typically -- yet another grim foreshadowing of Iraq with its Abu Ghraib and Afghanistan with its Bagram prison in cavernous structures at the old Afghan and Soviet air base-- when new Congressional questions began to be asked about the involvement of the U.S. military as well as the CIA in the Saigon regime's infamous "Tiger Cage" torture camps in South Vietnam, an issue that surfaced well before his tenure at the Pentagon but which arose anew in 1975-1976 after fresh revelations of US-aided torture and assassinations, Rumsfeld led the Ford Administration in blocking damaging disclosures until the issue eventually trailed off. It was one more plot of buried history -- along with a seedy CIA front, the Office of Public Safety, implicated in advising and abetting the secret police "renditions" and torture practices of client regimes worldwide until its quiet disbanding by Congress in 1975 -- with echoes into the twenty-first century.

Officially, the crumbling of discipline and performance in Vietnam would be blamed not on the military's long-festering venality and incompetence, but on the ready scapegoats of antiwar agitation and the larger social turbulence of the 1960s, a perfect fit with Rumsfeld-Cheney demonology. To the relief of the Joint Chiefs, the Secretary of Defense scoffed at, or swiftly suppressed, any institutional self-examination; yet the counterattack on critics was vicious. "Overlong in battle and emotionally unbalanced," was the way one Pentagon-kept military columnist smeared an officer of legendary heroism who publicly deplored service careerism.

As America gladly celebrated its Bicentennial under Gerald Ford's calming, anodyne post-Watergate presidency, the tide of self-awareness in the Pentagon was "allowed to recede," as a later study recorded, and officers "whose careers were deeply rooted in the polices and practices [of the war] finally prevailed." The latter included leaders of the 1991 Gulf War and 2003 Iraq debacle, most famously Colin Powell, who as a mid-grade careerist was personally involved in a whitewash of the My Lai massacre.

When a superintendent of West Point was earlier removed for his implication in the My Lai cover-up, he bid farewell to a dining hall full of sympathetic cadets with the old adage of General Joe Stillwell, "Don't let the bastards grind you down." Who the Superintendent's "bastards" were, the new Secretary of Defense and his unreconstructed high command had no doubt in 1975-1976.

In the siege mentality of Rumsfeld's post-Vietnam Pentagon, the besieging force was never a blindly misjudged nationalism, an intrepid insurgency, corrupt, untenable clients, or persistent myopia, folly, self-delusion, and ultimate self-betrayal of U.S. policy. It was the curse of wavering civilian masters at home -- craven Washington politicians and the old foreign policy establishment, especially Democrats -- and a public too easily swayed by the treachery of a mythological "liberal media." Humiliation in Vietnam had come not from colossal blunder, but from homefront perfidy, from the hoary stab in the back. "Do we get to win this time?" Rambo famously asks about his return to Vietnam, echoing in popular lore that denial of debacle.

It was Rumsfeld's historic legacy to rubber stamp the Great Evasion performed by America's military and sullen ideological right, as both fled headlong from the Vietnam reckoning. In the process, they all jettisoned responsibility, much as Saigon's American-bred profiteers cast cumbersome loot from their Mercedes sedans as they honked south through pitiful hordes of refugees just ahead of the final North Vietnamese offensive in the spring of 1975.

While U.S. foreign policy -- in heedless covert action as well as an orgy of globalism begun even before the fall of the Soviet Union, and then the reactionary mania loosed by 9/11 -- broadcast the seeds of new insurgencies (the prospects for what a handful of largely ignored theorists were calling "Fourth Generation Warfare"), serious study of counterinsurgency all but vanished from Pentagon planning and even from the service schools' curricula. The Iraq war would be years old and long lost by the time the Army revised, postmortem as it were, its little-read counterinsurgency manual written two decades before and anachronistic even then.

With Vietnam lessons unlearned and careerist blight as well as contract pillage uninterrupted, the military system's answer -- already emerging as orthodoxy under Rumsfeld in 1976 -- would be the simplistic, foolproof dictum, claimed by Colin Powell but hardly his originally, of fighting only with overwhelming forces, crushing firepower, and uncontested air cover (and even then having a precise "exit strategy" in place). This was, in sum, a version of General Taylor's "deter and win quickly." (As a "doctrine," it was as if the Army or Navy football team would only go on the field with its own rules, its own referees, and a 33-man team in the latest equipment to face an opposite 11 without helmets, pads, or the ability to pass.)

The so-called Powell Doctrine would soon be applied in settings allowing the post-Vietnam Pentagon's ever costlier, ever more "managed" high-tech bludgeon to be wielded against suitably feeble foes, without troublesome duration of engagement or the need for political understanding. Intelligence gaffes and the usual civilian carnage ("collateral damage") aside, the results looked encouraging in Grenada in 1983, Panama in 1990, and most notably the 1991 "turkey shoot" of the First Gulf War, carefully conducted to keep American casualties to the level of industrial accidents.

Fastidious, blameless brevity and detachment tended, of course, to sacrifice controlling the political outcome in any geopolitically meaningful arena -- as in, for instance, allowing Saddam Hussein to remain in power after his troops were expelled from Kuwait, and then, in defeat, to butcher Shiite rebels who, at the call of the first Bush administration in the persons of Baker, Cheney, Powell, and Scowcroft, thought the moment ripe to overthrow the tyrant themselves. Regrettably, they misread Pentagon imperatives. Chilled by a ghost they stoutly denied for decades, joint chiefs and defense secretaries would not repeat hot pursuit into North Korea or Vietnam's limited war of attrition -- not until the undertaker's fortuitous last chance at greatness arrived so explosively and irresistibly on September 11, 2001.

http://www.alternet.org/story/48085/

Former sailor sues Rumsfeld over detainment

December 19, 2006 CHICAGO — A former private security employee in Iraq said he was imprisoned by U.S. forces in a Baghdad military camp, held for three months without charges and denied access to an attorney, despite being an American citizen.

Navy veteran Donald Vance, 29, filed a federal lawsuit Monday against former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld for his role in overseeing the military prison system in Iraq.

In the lawsuit, Vance alleges that Rumsfeld’s “policies and directives are completely inconsistent with fundamental constitutional and human rights.”

Vance alleges he was held in “physically and mentally coercive conditions which are supposedly reserved for terrorists and so-called enemy combatants.”

Those conditions included being subjected to artificial light 24 hours a day, long periods of solitary confinement, threats of excessive force, being forced to wear blindfolds and hoods, and occasional deprivation of food and water.

Rumsfeld stepped down as defense secretary Friday.

Pentagon spokeswoman Cynthia Smith said the agency does not comment on pending litigation.

First Lt. Lea Ann Fracasso, a defense spokeswoman, told The New York Times in a story published Monday that Vance and a co-worker also taken into custody for a period were “treated fair and humanely.” In written answers to the newspaper’s questions, she said there was no record of the men complaining about their treatment.

Vance left the Navy in the late 1990s. After working for one security company in Iraq in late 2004 and early 2005, he took a job with another security company in the fall of 2005, but said he became concerned about some possible corrupt activity there.

On a trip back to Chicago for his father’s funeral, Vance said he went to the FBI and agreed to keep an agent there apprised of any strange activity he witnessed inside the company.

FBI spokesman Ross Rice said the agency does not confirm whether anyone has worked with the FBI.

Vance’s lawsuit said he worked for the FBI for several months before he and his co-worker decided to quit the security company.

With their identification cards seized by company officials, members of the U.S. military took the men to the American Embassy in Baghdad in April 2006. Vance and his co-worker were debriefed and given a place to sleep, but after a few hours were escorted outside and placed under arrest, according to the lawsuit.

In her answers to The New York Times, Fracasso said officials reached Vance’s FBI contact three weeks after he was taken into custody. Officials, however, determined that Vance posed a threat and he was held until a “subsequent re-examination of his case,” and Vance’s stated plans to leave Iraq caused him to be released in July, Fracasso wrote.

Vance spoke to reporters via a conference call in his attorneys’ office. He said he never was told what he was accused of doing wrong.

His attorney, Mike Kanovitz, said he believes authorities thought Vance could provide information about possible wrongdoing inside the security company for which he worked — but Vance already had provided that voluntarily to the FBI.

Vance’s lawsuit does not seek specific monetary damages. Kanovitz said more defendants could be added as the identities of Vance’s captors’ are learned.

Vance said he kept track of his time in prison by making notations in a Bible and hash marks on his cell’s walls and that his religious faith helped him through the ordeal.

Asked why his lawsuit only names Rumsfeld, Vance said he is certain the secretary knew of the detention of U.S. citizens in Iraq.

“It’s hard to believe they would treat any human being this way. I was shocked to see some of the things that were happening to local Iraqi detainees,” Vance said. “Regardless of their nationality or their religious background, I couldn’t believe this was happening to anyone.”

http://www.airforcetimes.com/story.php?f=1-292925-2433038.php

Rumsfeld bids farewell

- President Bush and outgoing Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld take part in a ceremony in honor of Rumsfeld on Friday at the Pentagon.

December 16, 2006 Outgoing Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was given a 19-gun salute and heralded by President Bush and Vice President Cheney as the best defense secretary the Pentagon has ever had.

Bush told a crowd of dignitaries, former Rumsfeld employees, lawmakers and senior defense officials that Rumsfeld was a “skilled, energetic and dedicated public servant.”

“The record of Don Rumsfeld’s tenure is clear: there has been more profound change at the Department of Defense over the past six years than at any time since the department’s creation in the late 1940s,” Bush said. “This man knows how to lead and he did and the country is better off for it.”

Bush cited Rumsfeld’s creation of a new defense strategy, a number of new commands, transformational initiatives and other accomplishments.

Reminding the audience of that “clear September day” on which the Pentagon and World Trace Center was attacked, Bush saluted Rumsfeld for leading the Defense Department into the war against extremists without losing sight of the bigger picture.

“As he met the challenges of fighting a new and unfamiliar war, Don Rumsfeld kept his eyes on the horizon and the threats that still await us as this new century unfolds,” Bush said. “Most importantly, he worked to establish a culture in the Pentagon that rewards innovation and intelligent risk-taking, and encourages our military and civilian leaders to challenge established ways of thinking.”

The farewell ceremony was held on the Pentagon’s Mall entrance, not far from where the audience was reminded several times how Rumsfeld helped the wounded after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The event was attended by many of the characters who had peopled Rumsfeld’s six-year tenure, including former Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, former Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Doug Feith, former Joint Chiefs Chairman Air Force Gen. Richard Myers, and Karen Hughes, Bush’s former advisor. Marine Gen. Peter Pace, current chairman of the Joint Chiefs, introduced Rumsfeld.

Rumsfeld’s wife Joyce, whom Pace presented with a distinguished service award for volunteerism, sat in the front row with his two daughters and son beside other friends and former Pentagon employees.

Cheney, who once worked for Rumsfeld when the two were in the Ford administration in the 1970s, said Rumsfeld was the “toughest boss I ever had.”

Rumsfeld’s record speaks for itself, said Cheney, who reportedly resisted calls to axe the Pentagon chief more than a year ago. “Don Rumsfeld is the finest secretary of defense this nation has ever had,” Cheney declared.

Rumsfeld, who has appeared almost emboldened by his own departure in public appearances in his last days, said this is a time “of great consequence” that marks only the beginning of a long struggle.

“It is with confidence that I say America’s enemies should not confuse American’s distaste of war, which is real, and which is understandable, with a reluctance to defend our way of life,” he said. “Enemy after enemy in our history has made that mistake to their regret.”

Rumsfeld said he is often asked what he will remember most during his time in office. He said it will be the service members who are deployed, who are recuperating from wounds in military hospitals, and who have fallen in battle, as well as their families.

“I will remember how fortunate I am to know you, to work with you and to be inspired by your courage and by your love of country,” Rumsfeld said.

Then, his voice cracking, he said: “You will be in my thoughts and prayers.”

http://www.airforcetimes.com/story.php?f=1-292925-2427425.php

Rumsfeld Says Farewell to Troops in Iraq

- Outgoing Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld shakes hands with well wishers following his speech during a town hall meeting at the Pentagon, Friday, Dec. 8, 2006.

December 10, 2006 BAGHDAD, Iraq (AP) - Outgoing Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld made a surprise trip to Iraq Saturday, just days after a bipartisan commission called the situation there "grave and deteriorating" and said the administration's policy wasn't working. "For the past six years, I have had the opportunity and, I would say, the privilege, to serve with the greatest military on the face of the Earth," Rumsfeld, 74, said in a speech to more than 1,200 soldiers and Marines at Al-Assad, a sprawling air base in Anbar province, the large area of western Iraq that is an insurgent stronghold.

"We feel great urgency to protect the American people from another 9/11 or a 9/11 times two or three. At the same time, we need to have the patience to see this task through to success. The consequences of failure are unacceptable," he was quoted as saying on the Department of Defense Web site. "The enemy must be defeated."

Rumsfeld also met with U.S. forces in Balad, 50 miles north of Baghdad, it said.

- Outgoing Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, left, accompanied by Joint Chiefs Chairman, Gen. Peter Pace, shakes hands with Pentagon personnel before his speech at a town hall meeting at the Pentagon, Friday, Dec. 8, 2006.

At least 2,930 members of the U.S. military have died since the beginning of the Iraq war in March 2003, many in and around Baghdad, and in hard-hit Anbar cities such as Fallujah and Ramadi.

In Baghdad, the U.S. military said Sunday that it couldn't immediately confirm Rumsfeld's visit or say how long he would remain in the country. The U.S. Embassy in Baghdad said it had no information since the military had handled the trip. The Pentagon refused to say whether Rumsfeld was still in Iraq or where he planned to travel next.

It was Rumsfeld's 15th trip to Iraq since the war began; he was last here in July.

Rumsfeld's trip follows an emotional farewell Friday at the Pentagon in Washington, where the defense secretary defended his record on Iraq and Afghanistan. He said the worst day of his nearly six years as secretary of defense occurred when he learned of the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse.

Rumsfeld's Pentagon appearance and his trip to Iraq on Saturday were among the few public appearances he has made since President Bush announced on Nov. 8 that he was replacing the defense secretary. His last full day will be Dec. 17.

- Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Marine Gen. Peter Pace, right, reaches out to shake hands with outgoing Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, after the two spoke during a town hall meeting at the Pentagon, Friday, Dec. 8, 2006.

Rumsfeld's farewell tour to Iraq follows a grim picture of the war that was presented this week by a bipartisan commission headed by former Secretary of State James Baker and former Democratic Rep. Lee Hamilton. The Iraq Study Group said its prescription for change is needed quickly to turn around a "grave and deteriorating" situation.

The commission called for direct engagement with Iran and Syria as part of a new diplomatic initiative and a pullback of all American combat brigades by early 2008, barring unexpected developments, to shift the U.S. mission to training and advising.

The report took direct aim at Rumsfeld.

Saying there has been a long tradition of partnership between the military and civilian leaders, the group said the "tradition has frayed" and must be repaired. It urged the new defense secretary, former CIA director Robert Gates, to "make every effort" to encourage military officers to offer independent advice.

Bush's national security team is debating whether additional troops are needed to secure Baghdad - a short-term force increase that could be made up of all Americans, a combination of U.S. and Iraqi forces, or all Iraqis, a senior Bush administration official said in Washington on Saturday.

Other options being debated for inclusion in what the president has said will be his "new way forward" include a revamped approach to procuring the help of other nations in calming Iraq; scaling back the military mission to focus almost exclusively on hunting al-Qaida terrorists; and a new strategy of outreach to all of Iraq's factions, whose disputes are fueling some of the worst bloodshed since the war began, said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because the disclosure of internal discussions had not been authorized.

http://apnews.myway.com/article/20061210/D8LTRCK80.html

Pentagon Intelligence Chief to Step Down

December 02, 2006 Stephen A. Cambone, the Pentagon's top intelligence official and a close ally of Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, will step down at the end of the year, becoming the first key department member to leave in the wake of Rumsfeld's resignation.

It had been widely speculated that Cambone, the undersecretary of defense for intelligence, would resign as the Pentagon prepares for the expected Senate confirmation of a new defense chief - former CIA director Robert Gates.

The Pentagon's intelligence-gathering has come under fire during Cambone's tenure, with critics accusing the Defense Department of trying to take expanded control over the nation's intelligence activities.

Cambone was in charge of intelligence when it was disclosed a year ago that a Pentagon database of suspicious activities contained the names of anti-war groups that had been found not be security risks. Cambone ordered a review of the program.

Pentagon spokesman Lt. Col. Todd Vician said Gates did not request Cambone's resignation.

"This was an independent decision," said Vician. "Dr. Cambone decided that now is a good time for a change to enable him to spend more time with his family."

Cambone came to the Pentagon with Rumsfeld in January 2001, and served in three other top level posts before taking over the intelligence job in March 2003.

http://www.forbes.com/entrepreneurs/feeds/ap/2006/12/01/ap3221894.html

Iraq's forces unready to fight

Number of battalions that do not need U.S. support has declined

November 19, 2006 WASHINGTON -- President Bush's policy of replacing U.S. troops with Iraqis has a major flaw. In the past two years, the number of Iraqi battalions ready to fight insurgents and militias without U.S. assistance has plummeted. Click here.

In June 2005, the Pentagon said three Iraqi battalions of approximately 800 soldiers each were ready to take on the enemy by themselves. By the fall of 2005, that had dropped to one battalion. By February 2006, that number had fallen to zero units, and by last June no more than one unit was capable of fighting without U.S. help.

And now, after millions of dollars spent training Iraqi forces, once again not a single Iraqi military unit is able to fight without American assistance.

Also, a declining number of Iraqi police units are able to perform basic policing operations.

The situation was acknowledged last week during hearings for Army Gen. John Abizaid, the top U.S. commander in the Middle East, before House and Senate lawmakers.

A total of 91 battalions of Iraqi troops are capable of battling insurgents and militias with U.S. troops providing backup. But American military commanders do not rate any of these units as capable of performing on their own.

Retired Marine Corps Col. Thomas Hammes, who managed bases and logistics for the training of Iraqi forces until 2004, said the capability of some Iraqi units is declining because Iraqis perceive the U.S. as preparing to withdraw forces. As a result, they are turning to militias for protection.

"If they believe we are leaving, the capability of the units will go down because they are seeking other options," said Hammes, a 30-year Marine Corps veteran. "We are sending a pretty consistent signal that we are getting out."

The fielding of independent Iraqi units -- those able to fight without the aid of U.S. firepower, intelligence, logistics or transportation -- is a crucial indicator of when large numbers of U.S. forces can begin leaving Iraq.

A contributing factor to the decline in independent units is that the U.S. hasn't provided the Iraqis with protective equipment.

"We have failed to give them much equipment after three years of training," said Hammes. "As it gets more violent, our guys are riding around in armored Humvees and armored trucks. The Iraqis are still riding around in pickup trucks."

Hammes added: "At what point do you as an Iraqi say, 'These guys (the Americans) are not serious'?"

The outlook for the Iraqi police isn't any more encouraging.

Army Lt. Gen. Michael Maples, chief of the Defense Intelligence Agency, said that the Iraqi police and its leadership in the Ministry of the Interior "are heavily infiltrated, and militias often operate under the protection or approval of Iraqi police to attack suspected Sunni insurgents and Sunni civilians."

Abizaid said last week that of the 27 operational Iraqi police battalions, only two are sufficiently able to take the lead in policing operations as long as Americans provide assistance.

"Back in October, six of them were in the lead. So you can see that we're not going in a good direction there," Abizaid said.

Rumsfeld and a mountain of misery

November 22, 2006 Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist, began life as a slave on Maryland's Eastern Shore. When his owner had trouble with the young, unruly slave, Douglass was sent to Edward Covey, a notorious "slave breaker." Covey's plantation, where physical and psychological torture were standard, was called Mount Misery. Douglass eventually fought back, escaped to the North and went on to change the world. Today Mount Misery is owned by Donald Rumsfeld, the outgoing secretary of defense.

It is ironic that this notorious plantation run by a practiced torturer would now be owned by Rumsfeld, himself accused as the man principally responsible for the U.S. military's program of torture and detention.

Rumsfeld was recently named along with 11 other high-ranking U.S. officials in a criminal complaint filed in Germany by the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights. The center is requesting that the German government conduct an investigation and ultimately a criminal prosecution of Rumsfeld and company. CCR President Michael Ratner says U.S. policy authorizing "harsh interrogation techniques" is in fact a torture program that Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld authorized himself, passed down through the chain of command and was implemented by one of the other defendants, Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Miller.

The complaint represents victims of torture at Abu Ghraib prison, the U.S. prison at Guantanamo. Says Ratner, "I think it is important to make it very clear that CCR's suit is not just saying Rumsfeld is a war criminal because he tops the chain of command, but that he personally played a central role in one of the worst interrogations at Gitmo."

Ratner is referring to Saudi citizen Mohammed al-Qahtani. An internal military report as well as leaked interrogation logs show how the Guantanamo prisoner was systematically tortured.

His attorney, CCR's Gita Gutierrez, described his ordeal on my TV/radio news hour Democracy Now!: "He was subjected to approximately 160 days of isolation, 48 days of sleep deprivation, which was accompanied by 20 hourlong interrogations consecutively. During that period of time, he was also subjected to sexual humiliation, euphemistically called 'invasion of space by a female' at times when MPs would hold him down on the floor and female interrogators would straddle him and molest him."

Gutierrez added, "At one point in Guantanamo, his heart rate dropped so low that he was at risk of dying and was rushed to the military hospital there and revived, then sent back to interrogations the following day and was actually interrogated in the ambulance on the way back to his cell."

The complaint follows one filed in 2004, which was dismissed. The 2006 complaint differs principally with Rumsfeld's departure as secretary of defense. Without the immunity of government office shielding him, Rumsfeld now falls under the jurisdiction of the German courts. Germany is among several nations that employ the concept of universal jurisdiction, which states that crimes against humanity or war crimes can be prosecuted by a state (such as Germany) regardless of the jurisdiction where the crimes were committed or the nationality of the accused. If an indictment follows, then Rumsfeld will have to be very careful when traveling abroad, as are former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

Torture is a noxious, heinous practice and should not be tolerated. Slavery was once legal and tolerated in the U.S. (it is still practiced in some parts of the world). But people fought back, organized and formed the abolition movement. Pioneering legal and human-rights organizations, such as CCR, aggressively and creatively are working to stop torture, and to hold the torturers and their superiors accountable. Ultimately, it will be the U.S. populace -- not the German courts, not the U.S. Congress -- that stops the U.S. torture program. Frederick Douglass summed it up most eloquently -- in 1849:

"If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will."

The owner of Mount Misery should take heed.

http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/opinion/293201_amy22.html?source=mypi

Rumsfeld's exit brings cheers, sadness

November 08, 2006 The winds of change swept from the ballot box into the Pentagon on Wednesday and Americans greeted the resignation of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld with delight, sadness - and a sense it was long overdue.

At Tazza Caffe in downtown Providence, R.I., shouts erupted when news of Rumsfeld's departure crossed the television screen as patrons followed the close U.S. Senate race in Virginia.

"Getting rid of Rumsfeld shows you how much momentum the Democrats have," said Darren MacDonald, one of Tazza's managers. "You wonder if the Republicans feel getting Rumsfeld out of there might make things easier for them."

Rumsfeld resigned hours after Democrats seized control of the House and came close to capturing the Senate as well, riding a powerful wave of voter discontent over nearly four years of a war in Iraq with no end in sight.

As an architect of the war, Rumsfeld had become a target of congressional Democrats and more recently some Republicans, with increasing calls for his resignation.

President Bush announced the departure at a news conference and said there would have been a change at the Pentagon regardless of the election results. He also acknowledged that GOP losses reflected voters' "displeasure with the lack of progress" in Iraq. Surveys at polling places showed about six in 10 voters disapproved of the war.

Lucia Cruz, a 61-year-old bank employee in Miami, said Rumsfeld should have quit months ago and that might have spared the GOP on Tuesday.

"The election was a message to the president to let him know that people were not happy," she said. "If Rumsfeld had resigned before the election, maybe the Republicans wouldn't have lost so many seats in Congress."

Michael Corso, a 36-year-old lawyer from Providence, dismissed the departure as "a day late and a dollar short."

But Erik Smith, a 37-year-old information technology manager from Coraopolis, Pa., said he was sorry to see Rumsfeld leave.

"I felt he did the best job he could with what he was given," he said. "You get familiar with someone and you think they're doing a decent job, then it turns around."

In Washington, many Republicans praised Rumsfeld's service, while some Democrats expressed optimism that a new Pentagon chief - former CIA director Robert Gates has been tapped for the post - could offer fresh ideas in dealing with Iraq.

Some voters had the same thing in mind.

"Maybe new blood will do something good that way as long as we focus on getting out," said Shane Mahoney, a 33-year-old Denver commercial real estate broker. "We should not have gone there in the first place."

But others were skeptical that a new Defense secretary would lead to a shift in Iraq war policy.

Erin McCabe, a 32-year-old real estate appraiser from Boston, said she thinks if Bush had actually been responsive to voters, he would have made the change sooner.

"The only problem is I don't see anything is really going to change in Iraq because of it," she said.

Silvia Lomas, a stay-at-home mother in Fresno, Calif., said she was happy to see Rumsfeld go.

"I voted straight Democratic yesterday because of Iraq," she said, "so I'm glad someone is finally taking some heat."

Gerald Butler, a 49-year-old courier in Boston, says he thinks Tuesday's election results and Rumsfeld's exit will clearly bring change - but it won't happen overnight.

"We need to give it time," he said, "because if we keep patting ourselves on the back, nothing will get done."

But Butler said he senses Bush has gotten the message.

"He has to listen now," he said. "He has to."

http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/national/1110ap_rumsfeld_nations_mood.html